Junos 50th anniversary: How we remember these award-winning hit singles

June 4, 2021

Share

aficionados are celebrating the 50th anniversary of . Known variously in Juno history as âBest Single,â âBest Selling Single,â and now â,â this award always garners attention.

The Junos and came into being at around the same time to promote Canadian culture to Canadians. Whatever the awardâs name, the winning song emphasizes Canadaâs place on pop musicâs world stage. Reflections on these songs, both personal and historical, make the music even more compelling. Hereâs a look at earlier years.

âCanât Feel my Face,â The Weeknd (2016)

If someone announced that they canât feel their face when theyâre with you, you would obviously think something was very wrong; you may even want to offer assistance to alleviate their discomfort. But not the female interlocuter in The Weekndâs song âI Canât Feel My Face.â

Instead, the song goes, âShe told me, âDonât worry about it/She told me/Donât worry no more.ââ The Weeknd exploits both the drama of the claim and the felt sense of human pity it evokes in the titular refrain, to which he quickly adds âbut I love it, but I love it, oh.â

Some admirers think the song is about The Weekndâs use of . Others believe the song is an ironic ode to The Weekndâs love interest at the time, model Bella Hadid.

Both interpretations can be simultaneously true; that is the very point and power of lyrical expression. The song is dark. Yet it makes us dance. It confesses a public taboo. Still, we bop.

Great lyricists, like The Weeknd, take our social privacies, place them on poetic display and elevate them so that listeners share, even if unwittingly, . So as much as the song is a catchy dance hit, it is an opportunity for cultural , on why, as humans, we are often addicted to experiences and people who are otherwise bad for us.

Vershawn Ashanti Young, University of Waterloo

'Dangerous,â Kardinal Offishall (2009)

Leading up to his 2009 Junos Best Single of the Year, Kardinal Offishall was already a legendary rapper and expert MC in Canada. Yet âDangerousâ was his introduction to the rest of the world. He became the first Canadian rapper to appear on the U.S. Hot 100 Billboard chart, .

The song is a classic radio hit in both arrangement and composition. At the same time, itâs a distinctive Toronto anthem. It fits into a larger legacy of Black Canadian youth music â part of what scholar Rinaldo Walcott argues is .

Offishall is a long-time ambassador for the AfroCaribbean diaspora in Canada. In âDangerous,â Jamaican patois gets mixed in with classic rap topics (âWhen she on the dance floor, gyal dem irate.â)

In this way, âDangerousâ represents a specific kind of belonging to Black Canadian culture that scholar Murray Forman notes is in AfroCaribbean traditions.

âDangerousâ was a cultural moment for Canadian hip hop due to its commercial success, but also its representation of the AfroCaribbean diaspora in Canada thatâs used hip hop as a way to fit into, rebel from and, as scholar .

Tamar Faber, York University

âBobcaygeon,â The Tragically Hip (2000)

Gord Downie, The Tragically Hipâs leader and lyricist, built the âSingle of the Yearâ in 2000 on the contrast between Toronto and rural Bobcaygeon, a name that is probably .

The narrator tells a story of having spent the evening with his lover, where they enjoyed âthe wineâ and âthe Willie Nelson,â a reference that conjures both the famous American singer and his decades-long crusade to have marijuana legalized.

In some

Verses one, two, five and six all open with a line that ends âyour house this morning,â emphasizing the centrality of the loverâs home. Driving âback to townâ in the morning sends the narrator âback to bed.â The quadruple rhyme â âHang,â âsang,â ârang,â and âtwangâ â drives the song to its crescendo.

There are troubling hints of violence turned against others and the self, with reference to â,â an âAryan twangâ and thoughts of âmaybe quitting ⊠leaving it behindâ â possibly implying quitting work drudgery or something significantly darker.

The song has become â. Yet as Downie makes clear, it could have been âany small town really.â

The song is a multi-levelled meditation on the interplay of personal intimacy, beauty, violence and despair â themes that Canadians must urgently grapple with at the centre of their colonial mythology.

Robert Morrison, Queenâs University

âYou Oughta Know,â Alanis Morrisette (1996)

Despite sweeping success at the 1996 Junos, more than 33 million sales worldwide and the reinvention in 2019 as part of an award-winning Broadway musical, Alanis Morrisetteâs âYou Oughta Knowâ is sometimes regarded ravings of an angry young woman, spurned by a lover and hysterical. But as musicologist Karen Fournier emphasizes, for Morrisette, The singer unapologetically bares her soul in âYou Oughta Knowâ â an action that challenges gendered norms and presumes a right to speak and be heard.

Writer notes that Morissetteâs music emerged in the wake of to the U.S. Congress and that supported victims of sexual harassment. In the recent musical, the plot directly and the .

Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw, Queenâs University

âNever Surrender,â Corey Hart (1985)

In the summer of 1985, if you were listening to the radio or watching MuchMusic, you inevitably heard or saw Corey Hart singing his hit âNever Surrender.â They are the same words that resonated and translates them into Cree syllabics to honour her own heritage, solidarity-building among Indigenous communities and to acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples are still here on Turtle Island.

âNever Surrender.â These are the words that Indigenous people still voice today in fighting oppression and to press governments to provide what ordinary Canadians take for granted, like clean water, health care and access to education.

In 1985, when the song was released after some and , Indigenous peoples finally had their constitutional rights confirmed just three years earlier, in 1982.

But what did these rights mean for a people still attending residential schools, still living in abject poverty? What did it mean if the legal system still held to the fiction of ?

There is an irony here. This is a celebrated song by a white, male Canadian singer suggests it is centred in his limited and privileged perspective on teenage angst. Yet, through an Indigenous lens, the lyric âAnd if your path wonât lead you home/ You can never surrenderâ is given the weight of history.

Armand Garnet Ruffo, Queenâs University

âRise Up,â Parachute Club (1984)

In the final months of 1980, two events marked â Ronald Reaganâs election as president of the United States and, within weeks, John Lennonâs assassination. The ideals of the 1960s were officially dead. A new neo-liberal agenda â favouring individualism, competition, and, ultimately, massive inequality â was taking hold and by 1983, arms control and escalating international conflicts were also on the minds of many. Even music had lost its teeth: punk was waning, video gamingâs popularity was up and record sales were down, prompting music critic Anthony De Curtis to conclude that, â.â

But music did matter, and, in 1983, the Parachute Clubâs release of âRise Upâ proved just that. Part of the songâs initial and enduring success is, of course, its infectious melody with its influences of Caribbean reggae and soca (the ). The all-important lyrics were specific enough to inspire feminism (âwomanâs time has comeâ), peace and queer rights (âfreedom to love who we pleaseâ) but broad enough to rouse all who listened.

, the song reflected a new hope in the era of the newly signed and, unsurprisingly, went on to become a queer anthem. In the Canadian video, the band, with a parade of youth, unabashedly and proudly danced through the streets of Toronto. In the face of personal adversity and international uncertainty, âRise Upâ helped many of us feel like we were visible, hopeful, and for a moment, free.

Kip Pegley, Queenâs University

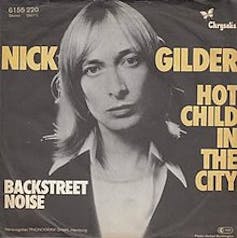

âHot Child in the City,â Nick Gilder (1979)

In 1979, ââ marked the second Best Selling Single Juno for Nick Gilder. His band, Sweeney Todd, scored the award two years earlier with â.â The week âHot Childâ hit the top of the Billboard charts was a big one for Canada as Anne Murrayâs â,â was No. 2. łÒŸ±±ô»ć±đ°ùâs international success led him to write songs for artists that included Joe Cocker and Pat Benatar.

łÒŸ±±ô»ć±đ°ùâs . Glamâs harder-edged are a precursor to punk, and many of its .

Energetic, infectious, though seemingly insubstantial songs by David Bowie and Gary Glitter of this era belie themes of heavy drug use and sexualized violence. Musically and thematically, âHot Child in the Cityâ bears some similarity to by Lou Reed, one of the grittiest writers, in his glam days.

Listeners have missed it for years, but Gilder discussed . His lyrics are critical of the street scene and the predators who drive it, starkly contrasting the bouncy, catchy pop music that accompanies them.

Robbie MacKay, Queenâs University![]()

________________________________________________________________

, Lecturer in Musicology, Dan School of Drama & Music, ; , Professor in English, Cross-appointed with Languages, Literatures and Cultures, ; , Professor of Music, ; , Postdoctoral fellow, Dan School of Music, ; , Queen's National Scholar, ; , PhD Candidate, Communication and Culture, , and , Professor, Departments of English Langauge and Literature & Communication Arts,

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .

The Conversation is seeking new academic contributors. Researchers wishing to write articles should contact Melinda Knox, Associate Director, Research Profile and Initiatives, at knoxm@queensu.ca.